What is Atopic Dermatitis?

"Eczema"

“Eczema” is a broad term which refers to a number of distinct skin diseases in addition to atopic dermatitis, such as hand dermatitis, contact dermatitis (allergic or irritant), seborrheic dermatitis, asteatotic or “winter eczema,” stasis dermatitis, nummular dermatitis and others. These may be loosely referred to as “eczematous dermatoses” because they share certain features in common, such as scaly, itchy, inflamed skin and certain microscopic skin changes, and they often coexist or overlap. But when most people say they or their child have “eczema,” they probably mean

atopic dermatitis.

Two examples of how Atopic Dermatitis may present itself on the hands and feet.

Atopic Dermatitis Basics

Atopic Dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing skin condition which is generally intensely itchy, and is associated with “atopy,” or a genetic predisposition to develop allergic diseases, such as asthma or allergic rhinitis (inflamed, runny nose, as in seasonal allergies). It tends to come and go, or wax and wane, with periodic eruptions called flares. In the acute or early phase of a flare, there can be seen redness, bumps and small blisters, with oozing and crusting. The intense itching leads to scratching, which can cause open wounds vulnerable to infection. When areas of skin have been affected by AD for some time, they become thickened, scaly, and can change in color, becoming lighter or darker than the surrounding skin. Dryness is another cardinal feature, and in certain areas, the dried-out, scaly, inflamed skin can split open, causing fissures which can be quite painful.

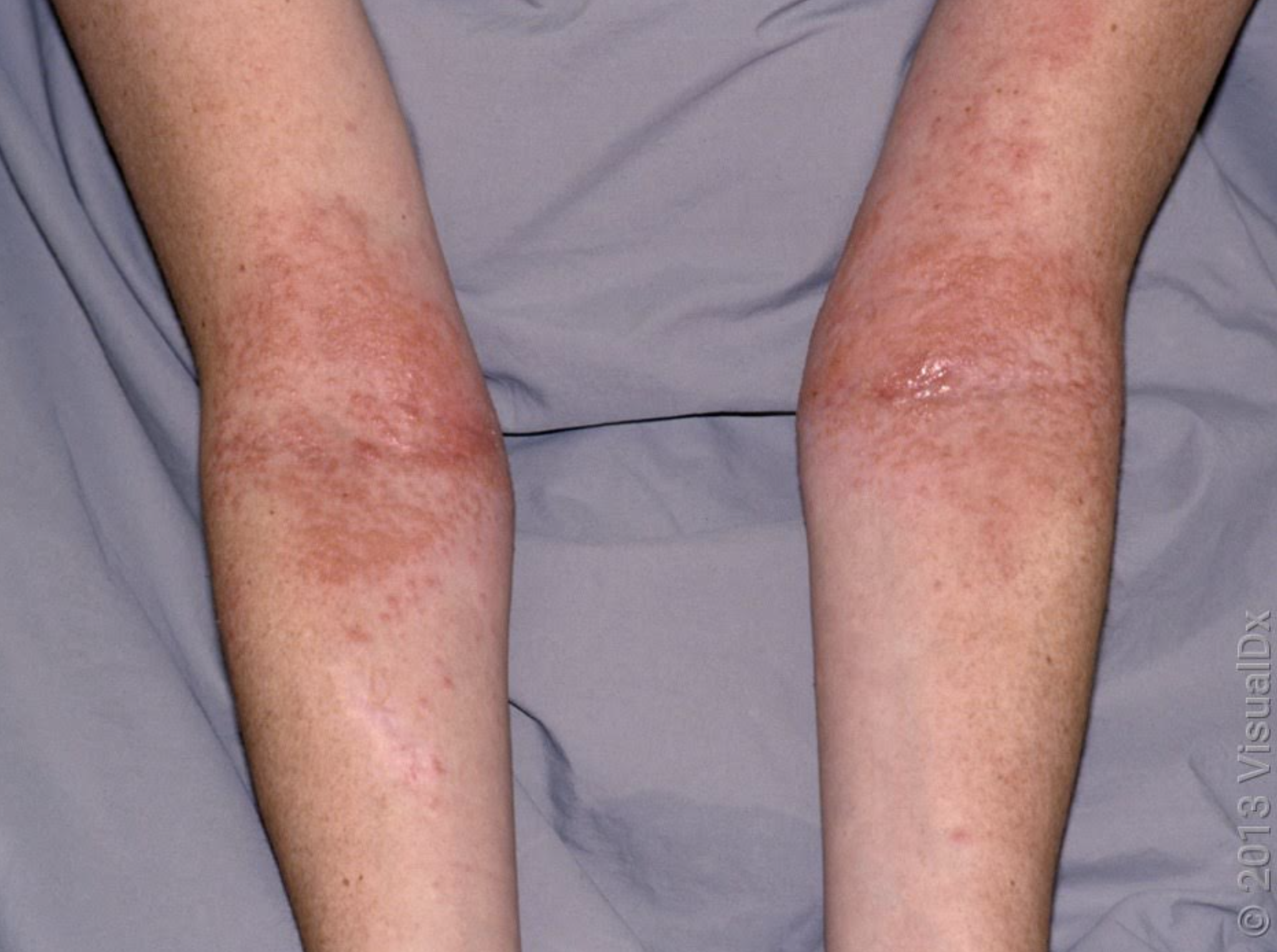

AD affects infants and children most commonly, with 85% of cases appearing within the first year of life, and 90-95% within the first five years. It is estimated that perhaps 10-20% of school-aged children in the US suffer from AD to some extent. In adults, AD is less common, with a prevalence of 1-3%; however, other eczematous dermatoses more common in adulthood can overlap and coexist with adult AD. It is common for it to appear in childhood, lie dormant for years or decades, and then reappear in adulthood. Perhaps 40% of children with AD continue to suffer persistent or recurrent disease as adults. In infants, AD tends to involve the face, head, torso and outer (extensor) elbows and knees. In children and adults, it more commonly involves the inner (flexor) creases of the elbows, knees and wrists. Hands and feet, head, neck and eyelids are also commonly affected, and the disease can also be widespread.

In skin affected by AD, there is disruption of the barrier function of the outermost layer of the skin, called the stratum corneum. When functioning properly, this layer holds the body’s moisture within, and provides a barrier against the environment. In AD skin, there is a deficiency of structural units and proteins essential to the barrier, such as ceramide and filaggrin, impairing its function. Water is lost through the skin, causing severe dryness; the defective skin surface also allows entry of environmental irritants and allergens, leading to an exaggerated immune response, with numerous immune cells infiltrating the skin and causing inflammation and itch. This then leads to the itch-scratch cycle: the more the skin itches, the more it is scratched, and scratching only makes it itch more.

The exact cause of AD is not fully understood, but the condition appears to arise from an interaction between both genetic and environmental factors. Multiple genes have been identified as statistically associated with AD, some of which affect the immune system and how the surface of the skin grows, but these statistical correlations are not the same as identifying the cause. Also supporting the genetic basis of cause is the pattern of familial inheritance. Most people with AD have family members with atopy (allergic rhinitis or asthma), and roughly one third have a family member with AD. Twin studies have found that if one twin has AD, the other is likely to have it as well, and more so for identical than for nonidentical twins. But even with identical twins, this association is roughly 85%, and the mechanisms of genetic inheritance and expression are not fully understood.

On the other hand, many environmental factors also appear involved in triggering and/or exacerbating atopic dermatitis. It is known that atopic dermatitis and atopy in general are more common in regions of the world which are more developed, urbanized, industrialized, and advantaged socioeconomically, such as the US. Also, within the US, it is more common in East Coast states than in the Midwest and Southwest, and more common in metropolitan than rural areas. It is also known that AD is becoming more prevalent globally to a degree that cannot be attributed to genetics alone. Much research is ongoing to investigate environmental triggers in order to prevent AD or lessen its severity.

Many environmental risk factors have been studied in relation to AD, and in most cases further study is needed to make sound recommendations. As mentioned above, rural living is associated with a lower incidence of AD. One explanation for this appears to be greater exposure to environmental pathogens, several of which appear to be protective against AD and atopy in general. This effect is also seen in children exposed to frequent infectious diseases through early day care. These exposures appear to cause the immune system to react differently to the environment later in life, with less likelihood of AD. Another explanation may be children in rural areas spending more time outdoors in the sun; UV light is known to be therapeutic for AD, with phototherapy being a prescribed treatment in some cases. Urban living is also associated with greater concentrations of air pollutants, especially traffic-related pollutants, and proximity to busy roads has been shown to increase the incidence and severity of AD. Indoor air pollutants are also implicated; active and secondary tobacco smoke exposure is of course a major trigger for asthma, but appears to be a risk factor for AD as well. Prenatal and maternal exposures are an area of focused research; AD prevalence and severity are associated with increased maternal stress during pregnancy, alcohol consumption, and a lack of healthy gut bacteria. We now know that healthy gut bacteria play an important role in the development of the immature immune system, and the primary source of a newborn’s intestinal microbiome is the maternal gut. Exposure to antibiotics in utero is implicated as a risk factor, and many studies have shown probiotics to be protective. Routine vaccinations for mother or child have no effect. Many dietary factors have been studied, with the most supported protective factor being maternal dietary fish, probably because it is rich in omega-3 fatty acids, also available in fish oil and prenatal supplements. Breast-feeding for the first 3-6 months of life is also probably protective. Many others factors have been studied, and the field of research is complex. Most likely, none of the environmental risk factors discussed are sufficient to cause AD without an underlying genetic predisposition.

Atopic Dermatitis may present itself on the inner (flexor) creases of the elbow.

General Measures and Treatment

While there is no definitive cure for AD, it can be well-controlled. The goal of treatment is to live one’s daily life free from itchy, inflamed skin, with occasional flares being minimalized and short-lived. The primary goal is to use daily measures to prevent flares from occurring; then, if and when a flare occurs, to treat it appropriately to end symptoms quickly.

As disruption of the barrier function of the skin is central to AD as described above, the mainstay of primary prevention of flairs is to restore and protect the skin barrier through the frequent, liberal use of emollients or moisturizers. People with AD should keep moisturizer with them at home and wherever they go, in their car, purse, backpack, and apply it multiple times throughout the day. This is most effective right after a shower, bath, or hand-washing. When showering, it is best to avoid long, hot showers. Swimming in chlorinated pools is not discouraged, but it is best to shower immediately afterwards, and then to apply moisturizer.

It is also best to avoid harsh soaps and detergents. These contain ingredients which further strip the skin barrier; use gentle cleansers instead, and carry your own with you when out of the house. Harsh chemicals, fragrances, dyes, scented salts and oils can cause irritation and should be avoided. Laundry detergents designed for sensitive skin should be used. Cotton clothing is preferred over wool or rough synthetic fibers. Occupational exposures to chemicals can pose a challenge, and it may be helpful to wear gloves when performing certain tasks.

When a flare occurs, the first line pharmacologic treatment will likely be a prescribed topical steroid cream. People often ask about side effects from using these medications. It is true that abuse or overuse of topical steroids over time can have side effects, most notably skin atrophy or thinning, because they inhibit collagen formation. With children, of course, special care is taken to use the least potent formulation necessary. Also, the skin differs in various areas of the body, so a topical steroid which is appropriate to use on the trunk, arms or legs, may be too strong for the face, or in skin folds, such as the underarms, groin, or beneath the breasts. But the goal of minimizing this risk by using less potent steroids must be balanced with that of gaining prompt, adequate control over a flare with more potent ones. It would be worse to undertreat a flare, using a weaker topical steroid for too long, than to use a stronger one for only a few days. Your dermatologist will know what formulation is appropriate for you or your child, and will give instructions for how to apply them. You may have more than one steroid for different areas of the body. Treatment will generally be approached step-by-step, starting conservatively and escalating if necessary. In most cases, topical steroids can be applied twice daily when needed for a flare, for no longer than two weeks in a row. People with frequent flares may also use topical steroids twice weekly in troublesome areas for prevention.

Another commonly used medication to help break the itch-scratch cycle is a sedating anti-histamine, such as prescription hydroxyzine or over-the-counter diphenhydramine (Benadryl). This can help relieve itch at night, and is most useful for patients whose itch prevents them from falling asleep. Non-sedating anti-histamines such as cetirizine (Zyrtec), fexofenadine (Allegra), or loratadine (Claritin) can be helpful during the day, but less so.

When scratching leads to open wounds on the skin, especially in children, care must be taken to avoid or treat possible infections. Adults should resist the urge to scratch and use topical medications as necessary to control itch. If a young child is scratching and causing open wounds, this is a clear sign that the child’s AD is inadequately controlled, requiring an escalation in treatment. Keep nails cut short to minimize trauma. Bleach baths can be helpful a few times a week. Bleach is antibacterial, and a diluted bleach bath can reduce eczema symptoms and prevent skin infections. To prepare a bleach bath, use a half cup of bleach for a full bathtub of water, or a quarter cup for a half tub. Only use plain bleach, and not a splash-less or fragranced type. Antibiotics are also often prescribed to prevent infections.

If general measures and topical steroids are not enough to control AD, there are many other prescription medications available. Non-steroidal topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus can be used alone or in conjunction with topical steroids in an alternating regimen. When these are inadequate, your dermatologist may seek approval for more advanced non-steroidal topicals such as ruxolitinib (Opzelura), approved for patients 12 years of age or older, or crisaborole (Eucrisa), approved for adults and children as young as 3 months of age. When these fail, systemic medications in the form of pills or injections are also available, and new and improved formulations are being approved rapidly each year. Dupilumab (Dupixent) is an injectable biologic approved for adults and children 6 months of age or older. And more recently, once daily oral medications of a class called Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have been approved such as upadacitinib (Rinvoq) and abrocitinib (Cibinqo).

Your dermatologist will know how and when to escalate your treatment, step-by-step, until adequate control is reached. But you can rest assured that, by combining the primary preventive measures and pharmacologic treatments described, you or your loved one can be free of daily itch and flares, and enjoy an improved quality of life.

Nicholas Tocco, PA-C

About the Author

Nicholas Tocco, PA-C is a graduate of Florida Gulf Coast University, where he completed his Master of Physician Assistant Studies degree. Trained in general, surgical and cosmetic dermatology, he is now proud to join the OnSpot Fort Myers team. He is a member of the American Academy of Physician Assistants, the Florida Academy of Physician Assistants, and the Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants. He currently resides in Naples with his wife and four children.

MEDICAL ADVICE DISCLAIMER

The information provided on this site is for educational and informational purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. OnSpot Dermatology is not providing personalized medical assessments or recommendations for individual cases in this post. The content presented here is based on general knowledge and should not be considered a substitute for a consultation with a qualified healthcare professional. The use of information provided is solely at your own risk. OnSpot Dermatology and the author make no representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding the completeness, accuracy, or usefulness of the information presented. By reading this post, you agree to the above disclaimer and understand that any action you take based on the information provided is at your own discretion. If you have specific questions or concerns about your skin or any medical condition, please consult a healthcare professional for a personalized assessment and recommendations.